Jounce

Jounce

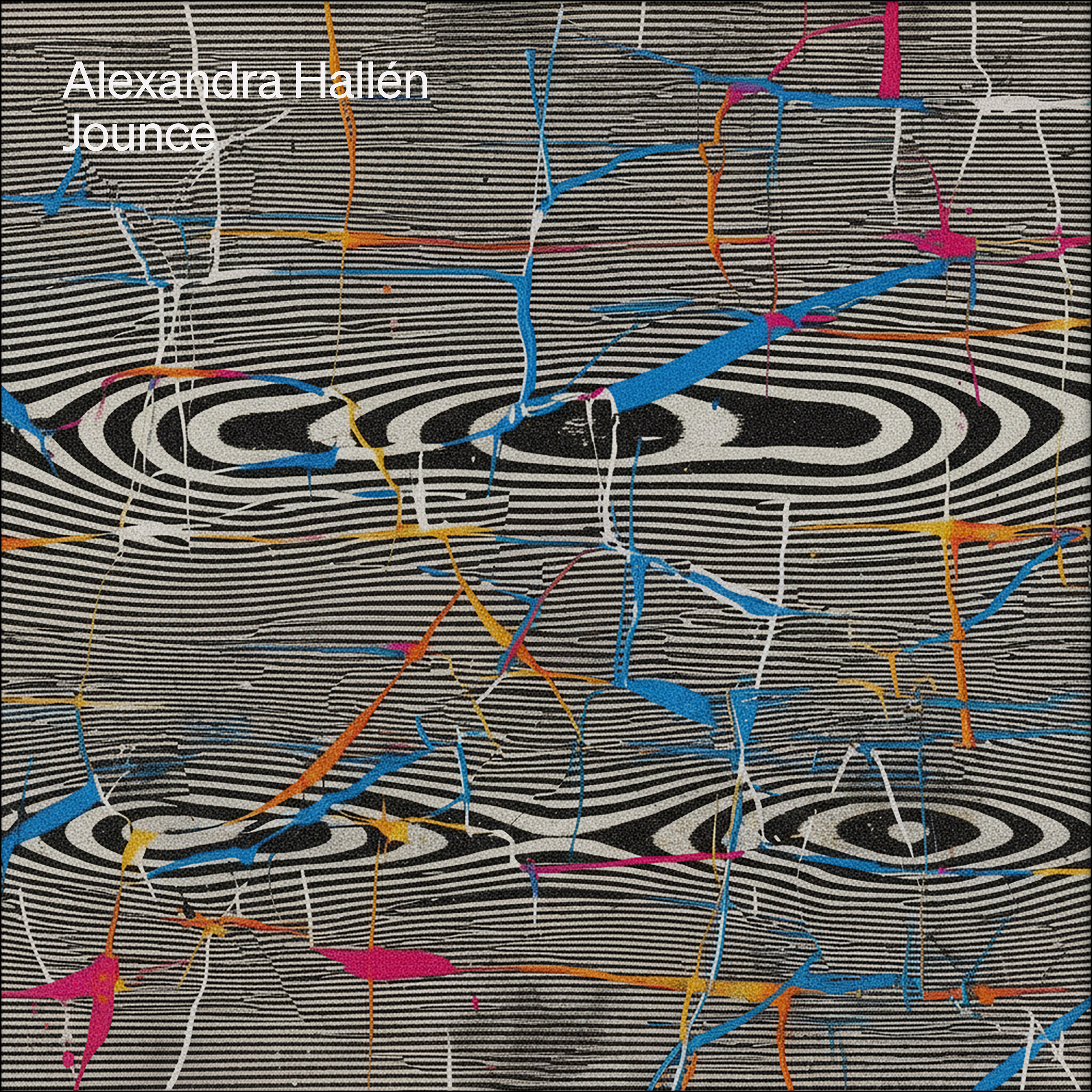

On Jounce, it is as if cellist and performer Alexandra Hallén navigates the visceral landscape of a fever dream, exploring the limits of memory and physical extremity. From the intimate, self-soothing vocals of Simon Løffler’s Graduale to the jagged, amplified outbursts of Jexper Holmen’s Vespa Crabro, Hallén pushes her craft to the edge; a journey culminating in the title track’s use of two bows, reaching a space where it is as if the fever finally breaks.

-

mp3 (320kbps)69,00 kr.mp3€9.23 / $10.9 / £8.09Add to cart

-

FLAC 16bit 44.1kHz79,00 kr.CD Quality€10.57 / $12.48 / £9.27Add to cart

-

FLAC 24bit 96kHz105,00 kr.Studio Master€14.05 / $16.59 / £12.31Add to cart

| 1 | Graduale | 7:06 |

12,00 kr.

€1.61 / $1.9 / £1.41

|

| 2 | Jounce | 5:48 |

12,00 kr.

€1.61 / $1.9 / £1.41

|

| 3 | G.T.S.C. | 5:13 |

12,00 kr.

€1.61 / $1.9 / £1.41

|

| 4 | Cadenza | 4:38 |

8,00 kr.

€1.07 / $1.26 / £0.94

|

| 5 | Vespa Crabro | 1:10 |

8,00 kr.

€1.07 / $1.26 / £0.94

|

| 6 | Childhood Tapestry Seen During Fever Hallucinations | 11:10 |

16,00 kr.

€2.14 / $2.53 / £1.88

|

Fever Dream

By Tim Rutherford-Johnson

‘May the lilied throng of radiant Confessors encompass thee … ’: the text for Simon Løffler’s Graduale (2009) comes from the Catholic Ordo Commendationis Animae, the Rite for the Commending of a Departing Soul. Typically, these words are said as part of the Last Rites given to the dying. They inhabit a semi-public role: part private intercession, part public mourning. In James Joyce’s Ulysses, Stephen Dedalus recalls them being spoken around his mother’s deathbed. The twist in Løffler’s setting is that the singer sings with hands clasped tightly over her ears: this gives, first, a certain instability to the sound, which cannot be checked or adjusted against its presence outside the body; and second, a sense that the singer is praying not for the soul of someone else, but for their own: that the prayer is an act not of commendation, but of self-soothing, perhaps even an urgent one.

Placed among the other works on this release, Løffler’s fragile melody acts as a delicate, if fleeting, oasis of calm. The wider landscape is established by Alexandra Hallén’s partly improvised re-enactment of a childhood fever dream, Childhood Tapestry Seen During Fever Hallucinations (2018). Hallén has a photo of the wallpaper: its white, stippled surface broken by a series of apparently random cracks. The largest pierces right through the surface, revealing behind it an ominous, black void. In her playing, Hallén places her body at the centre of this troubling memory. Against a churning metallic sound, like the turning of a demonic machine, she beats against her cello, as if trying to control and exorcise her fever. But as the fever grows, the sound passes to her voice – first in groans, then in screams, then in sobs. In that way that fever dreams do, mind, body and external reality meld into one, a single, thrashing nightmare.

The music is uniquely frightening, but its gestures provide a basis that Hallén abstracts and explores further across her recital. On the page, Jexper Holmen’s G.T.S.C. (2018) appears an intricate study in double- and triple-stopped chords, but in practice (the title is an abbreviation for ‘gennemgribende tungt strukturskabende cellosonate’, or ‘radical, heavily textured cello sonata’), intense bow pressure transmutes those harmonies into stabs of coloured noise, out of which solitary notes or battered allusions to musical motif occasionally break free. In the same composer’s Vespa Crabro (2004), similar gestures are turned towards an evocation of the European hornet – an alien creature, grotesque and fascinating. Encountering a hornet up close is to bump into a fever-like distortion field: the same shape and colour as a wasp, but somehow made at the wrong scale. Holman’s brief portrait captures that distortion of scale, the insect’s buzzing and skittering magnified out of all proportion by the resonance of the cello and the ferocity of Hallén’s movements.

Christian Winther Christensen takes similar materials a step further into abstraction. A cadenza is typically a moment of light relief within a concerto; a moment outside the wider musical argument for the performer to briefly let their hair down, show off a little. Christensen’s Cadenza (2013) is certainly virtuoso territory, an endlessly changing landscape of extended techniques for bow and hands. (Every sound, even the strange rising sine-tone effect, is produced acoustically.) But their compilation seems to fracture rather than assert the dominance of the soloist. Her instrument is pulled apart into its constituent units, each one held up for inspection; her own body is barely ever allowed to enter that seamless flow that marks the truly virtuoso performance. Paradoxically, the only time it is – and this is the piece’s dominant motif – is to make the flattest, emptiest sound possible: rows of middle A quavers with banal up-down bow-strokes. Stuck in a series of broken loops, Christensen’s Cadenza recalls a character from a Samuel Beckett play, struggling to build past glories from shattered, ruined fragments.

In engineering terms, a jounce, or snap, is the fourth derivative of position or, to put it another way, a measurement of how quickly the acceleration of a body in motion changes. (If jerk – the third derivative of position – is what you feel when your car starts to accelerate, jounce is what occurs when it begins to jerk.) Juliana Hodkinson uses ‘jounce’ in the more common sense of a combination of ‘bounce’ and ‘jolt’. The main rhythmic gesture of her piece Jounce (2016) is a col legno battuto, or the ricochet effect produced by bouncing the wood of the bow on a string. Using two bows in contrary motion, Hallén can turn a basic physical phenomenon into a range of colours and effects. And, in a nod to the nested forces at work in the scientific sense of jounce, each bow is fitted with a small cat-collar bell, which jangles to its own rhythm in response to the rhythms of the bouncing bow (which itself bounces according to the movements of the player’s arms and hands).

By focusing calmly and assuredly on just one thing, it is as if the fever breaks, and we are jolted back into reality.

© Tim Rutherford-Johnson, 2026

Tim Rutherford-Johnson is a writer with a focus on new music. He is the author of the widely praised Music after the Fall (University of California Press) and The Music of Liza Lim (Wildbird), and has co-authored Twentieth-Century Music in the West (Cambridge University Press).